The Roles of Private International Law in Monetarism in Supporting the Economy in the Post-COVID-19 Era: Can law institutions help firms and government agencies out with international legal lessons?

By: Xaypaseuth Phomsoupha, PhD

Managing Partner, Principal Solicitor-at-Law

Researcher & Author

This revised abridged article may be apt for Laotian corporate finance practitioners, post-graduate students, and academic teaching staff in the Lao universities that provide international economics and finance law courses.

1. Introduction

Humankind exchanged goods and services for which commodities served as a measure of value and medium of exchange thousands of years ago. As social organisations dynamically evolved, humankind interacted, made rules, and created media of exchange for chattels, referred to as money, to suit the gainful environment.[1] The money then lying at the heart of finance has dynamically expanded in parallel to the evolution of social law to frame the application of the means of value. Financial regulators in certain jurisdictions have diversified money into various forms, some of which are not even called “money”, representing the value of goods and services and means of payment.[2] Corporations claim their role in making money for the economy, regardless of how the private sector spearheads the system.[3] People have argued whether the law functions in money creation, distress alleviation, or both.

In this paper, the author brings the attention of readers, including Laotian law practitioners and academic teaching staff, to money creation in championing a strategy to redress financial distress resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic in Laos. The economy must create money and secure jobs for people living in the jurisdictional territory per the generally acceptable macroeconomic setting.[4] With the advent of artificial intelligence in banking and contract formation, the money creation-related sectors must open wide to modernisation and internalisation.[5] The author relates this article to a Lao government initiative to sign up to membership in HCCH and accession to the most necessary conventions on private international law in anticipation of enhancing the national economy development.

2. What is Money?

2.1. Money Definition

In the past, money merely meant the wealth of individuals, companies, or states, with which actors could buy goods and services for consumption or utilisation to produce goods and services they did not produce.[6] The wealth was, in turn, measured by a unit of fiat money established for each economy. Commodities existed when one made, for instance, a ton of wheat or a pair of shoes, thereby increasing the producer’s wealth by virtue of his or her proprietary products.[7] Money, known as M1, M2, and M3, comprises currencies and coins, demand bank deposits, and credits extended by banks or financial institutions.[8] Money was initially confined to a store of value and medium of exchange. Subsequently, money in M5 and M6 appeared in the money circulation,[9] and those denoted as M7 and M8 decentralised in the cryptocurrency family and whatever may add up to their value functions. Many state banks printed currency and coins, while commercial banks and financial institutions loaned money to eligible borrowers regardless of whether the latter were individuals or entities.

For the purpose of the analysis herein, money piggybacks on the law of values, transformation, quantities, and volumes of goods and services into units of a currency of a particular state and beyond its border.[10] In the modern economy, money is built upon the preceding value principle by diversifying credits, which may be valued ex-post or ex-ante.[11] Equity investors are obligated to inject financial contributions quantified in shares,[12] as recorded in a corporate account,[13] and debt investors or creditors grant loans to the borrower company; in-kind equities and in-kind loans are then accounted for in monetary terms. Although each capital, equity, and debt denote its application differently, the terms encompass money for measuring the volume of funds businesses utilise to produce goods and services expressed in money next in line. Otherwise, a minimum value of the company’s net property is determined in a currency unit when the company is liquidated.[14] Money gives rise to currency growth as businesses expand and decrease upon liquidation.

With respect to money creation, the author precludes money falling into the cryptocurrency family from the analysis herein, given that its functions are limited in many aspects in the Lao jurisdiction if compared to M1 to M6. Likewise, investment in stateless cryptocurrency is not illegal and risky; nonetheless, businesses in many jurisdictions around the globe have not fully utilised money of this type in day-to-day transactions.[15] Thus, conventional money categorised under the existing conventions remains within the central theme of the analysis.

2.2. Investment Grows Money for the Economy

Keynesian economists suggested that money functions range from a store of value to a unit of account and a medium of exchange.[16] Modern economists expand money functions as a standard of deferred payment, whereby money units accounted for today will be accepted by future payees, considering the time value thereof.[17] The deferred payment function applies to financial analysis whereby an investor can predict the future value of incomes he or she will receive upon investment in today’s equity.[18] Hence, the quantitative aspect helps determine the accountable value of assets expressed in today’s monetary terms or the future.

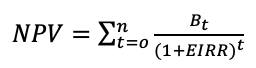

In the following assumption, a limited liability company established with a capital comprising equity expressed in nominally valued shares and debt capitalised at the startup plans to invest in a goods-production project.[19] A corporate finance specialist predicts the future value of the project cash flow by applying a financial formula to measure future products valued in monetary terms at the startup or any point during the production phase.[20] The procedure of the cost-benefit analysis is given below:[21]

Where;

Bt denotes net profits, which the company expects to receive during the preferred time horizon t, usually equal to or longer than the debt repayment period;[22]

NPV is the net present value representing today’s value of the future incomes, which the company expects to receive during the period “t”. To estimate NPV, a financial specialist shall apply the net profits accrued from lawfully declared dividends; otherwise, the corporate management faces legal consequences.[23]

EIRR means the Equity Internal Rate of Return, which is the cost of equity money per se; in deriving EIRR, one must solve the above equation assuming NPV equals 0.[24]

In interpreting the financial criteria, the corporate management looks at NPV, EIRR, and an average debt service coverage ratio (“ADSCR”) functioning as follows:

(i) NPV indicates the project’s profitability only when it carries a positive value; a high NPV value signifies the attractiveness of the investment.[25]

(ii) EIRR demonstrates how profits return to shareholders upon equity investment allotted in cash or monetary value.[26] The company will not invest in the planned project when EIRR is lower than a deposit interest rate. Nonetheless, when EIRR is higher than the prevailing borrowing rate, the shareholders will be willing to invest their equity assets in the planned project.[27]

(iii) ADSCR bespeaks the Average Debt Service Coverage Ratio derived from averaged net profits from startup to the end of the debt service period (“pds”) divided by the average debt service during pds.[28] When ADSCR is equal to or higher than 1.3:1, the company’s receivables are solid, and the cash flow is prospective, making appetite for creditors to grant loans to the company.[29] However, when ADSCR is less than 1.3:1, the project is not bankable, and no loan is created.

(iv) In the event that the company does not decide to invest in the planned project for any of the above reasons, no loaned money is functional. The analogy of effectuating valid securities is translated into a significant capital investment increase in corporate finance.

Project finance in significant projects in Laos has followed international practice, although equity and debt finance emanate from foreign-based jurisdictions. The foregoing formulae are undoubtedly applied to determining financial criteria acceptable to all stakeholders domiciled in legal systems different from the host.[30] Furthermore, most financing agreements of the underlying businesses are governed by and interpreted in accordance with English law, which functions differently from the civil codes asserted in Laos.[31] Under such circumstances, the legal arrangement must be internationalised by integrating into an international setting on a broader spectrum so that monetarism goes in line with legalism.

2.3. Credit Extension Increases Money in Circulation

Given the delimitation herein, money creation is built upon the tenet of value, translating in-kind equity and securities into monetary terms.[32] Economically, when a creditor extends credits, whether expressed in a currency or a commodities quantity, to a borrower company utilising such loans as the capital expenditure to produce goods or provide services, new money tends to exist and increases in circulation.[33] Financially, investors deal with money creation by diversifying credits extended by commercial banks and financial institutions to borrowers based on the borrower’s credibility.[34] When a newly invested project creates additional jobs and revenues, one may argue for other money creation due to a company’s investment.[35] Investors must put adequate capital at the right time to attain progressive investment results.

The financing shall be comprehensive when participants comprise shareholders, creditors, securities takers, and insurers.[36] Several creditors usually syndicate a large number of loans granted to a borrower for high-valued investment. A proper ratio between equity and debt and adequate risk management dictates sound financing for modern corporations in the current financing environment.[37] While corporate shareholders are liable for the equity assets, creditors and insurers share the risk of lending large amounts of money to the borrower company.[38] In one transaction, the abovementioned parties must safeguard their financial interests, considering risk and reward. In securing a bank loan, the borrower company must place equities with other collateral packages as securities in favour of creditors.[39] For a termed loan, creditors set interest rates, related lending fees, a mode of principal repayment, a debt servicing period, and other conditions contingent upon the borrowers’ credibility.[40] When borrowers fail to repay principal and interest payments as they fall due, the lenders have the full right to realise the posted securities assets in accordance with a court decision.[41] Thus, money in a financial system can increase or decrease due to securitisation and loaning.

HM Treasury can create money, and the Bank of England influences the money supply in the Kingdom. The terms of secured and unsecured loans relate to assets, which the borrower companies place in favour of lending parties.[42] Generally, debt instruments entail bonds, notes, and commercial papers, which a borrower makes available for the parties to lend the money.[43] Debt securities represent money loaned by the debt obligations holders to the securities issuers upon a premise to return the same amounts plus premium profits to the former when the securities fall due.[44] People generally accept that lending and making securities, bonds, and notes countenance businesses making new money in an economy.[45] However, one should bear in mind that not all lending and securitisation increase the money supply in the economy.

3. Implications in the Context of Money Creation in Respect of Government Measures to Support the Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis

3.1. Measures Relating to Money Creation for Countering the Financial Shocks

The COVID-19 shocks frustrated the operation of many states’ financial systems. The UK financial sector, with no exception, has been adversely impacted by the pandemic crisis over the past years.[46] The government has taken numerous measures to curb the incident and, at the same time, restore financial stability to put the financial sector in the same position as it would have been if such a crisis had not occurred. Since 2020, the government has announced numerous measures in respect of supervision and fiscal and monetary policy;[47] nonetheless, this paper presents some selected measures relating to money creation.

At the OECD level, country members concede that the pandemic has threatened the health of human actors, including those working at banks and financial institutions.[48] The prudential approach to avoiding risks was well taken following the COVID-19 shock. After much deliberation, the Basel Committee agreed to modify commercial banks’ financial risk by readjusting downward minimum capital requirements effective January 2023. However, the application of Basel III macroprudential tools by the EU and the UK posed numerous questions as the magnitudes of the COVID-19 shock have varied from place to place.[49] The UK government established the Independent Evaluation Office (“IEO”) to supervise the FMI operating in its financial jurisdiction.[50] The Bank of England welcomes IEO’s recommendations regarding objectives and responsibilities for the Bank to improve its management of the entire UK banking sector.

3.2. Fiscal and Monetary Policies

With respect to fiscal measures, HM Treasures and the Bank of England announced on 17 March 2020 that the two institutions coordinated to introduce a COVID-19 corporate financing facility, whereby the institutions were willing to buy commercial papers with a year-long maturity issued by corporations.[51] The government’s action initiates the money supply to the UK economy and hence supports businesses to smooth out liquidity with respect to the disbursement of salaries to the workforce and clearing claims of the contractors, which were deferred or disrupted during the crisis, as the case may be.[52] On 3 April 2020, the Chancellor encouraged action by announcing the provision of loans to private businesses hampered by the COVID-19 crisis.[53] Following the announcement, HM Treasures approved more than GBP90 million in loans for around 1,000 SMEs.[54] The UK SMEs have the full right to realise loaned monies as if the loans were the products to which the provider kept the title.[55] The responsible government agency has timely pursued the two selected fiscal measures; nonetheless, a supervisory body shall monitor the implementation to ensure that the budgetary policy operates consistently with other efforts.

With respect to monetary measures, the Bank of England introduced a new term funding scheme in which the Bank purchased low-interest corporate bonds of the aggregate amount of GBP10 billion, with which commercial banks and financial institutions increased business and individual investment.[56] The low-interest loan scheme helps SMEs sustain their business during a challenging time due to the pandemic. The Bank of England further took coordinated action with the central banks of Canada, Japan, the EU, and Switzerland to enhance the provision of US dollar repo operations.[57] The repurchase of US-dollar-dominated debt instruments facilitates foreign currency circulation in the UK economy to a great extent.

3.3. Legalistic Approach

Following the disintegration of the British economy from the EU coupled with the post-COVID-19 effort, alternative investment funds in the UK share only a fraction of the advanced economies.[58] Many businesses dealing in equity investment continue restructuring their partnerships with non-UK investors, thereby adopting a new investment strategy to cope with the change in the legal environment. One should bear in mind that private equity has some specific criteria with respect to maximum amounts for the investment size and eligibility investment nature.[59] Brexit, in turn, has given entrepreneurs domiciled in the UK better opportunities for assessing private equity investment from non-EU sources with fewer restrictions than when the UK economy was an integral part of the EU thanks to international arrangements put in place.[60] Arguably, Brexit may bring more opportunities for UK-based partners to deal with other markets in the US and advanced economies in Asia.[61] In creating the new investment strategy, equity houses shall diversify their funding sources from different jurisdictions that pose less or no constraint to the UK market.

In Laos, the Bank of Lao PDR is, with no exception, to oversee all commercial banks and financial institutions operating in the Lao jurisdiction. Unlike the UK, as the Lao PDR has imported equity funds and debt finance, state action must attend to the salvation of businesses by boosting their financing capacity in different large-scale projects that can leverage incomes for the economy per se.[62] Most capital in the form of equity and debts available for investment in developing economies like Laos have originated from EU sources.[63] Integrating the bank system into BASEL II and BASEL III has already paved the way for international financial institutions to bring funds into the country.[64] However, the arrangement may not suffice to mobilise funds from all possible sources in the eye of the law. In the absence of supporting conventions under the ambit of private international law under HCCH, for instance, businesses have had no direct access to capital markets unless transactions were done through a fronting arrangement with commercial banks domiciled in the region.[65] The banking operation has been subject to no less expensive charges in addition to endless prerequisites imposed on borrowers having a centre of interest domiciled in non-signatory states to the conventions.[66] Furthermore, when a difference between the financing parties arises, non-convention arbitration rules and forum non conveniens add up costs to the borrowers to the extent of disadvantageous dispute resolution.

The Lao state has employed fiscal and monetary policies to regulate its economy, evolving through different cycles. The state’s financial infrastructure with respect to artificial intelligence and relevant conventions must, from time to time, be upgraded to streamline the modus operandi with the rest of the world.[67] Laos’s economy must attend to integration with international institutions should it want to attract more funds to promote development, rather than merely relying on grant aids, which have been lingering on these days.[68] The available state’s natural assets can leverage considerable volumes of investment capital only when the financial and legal infrastructure put in place is commensurate with the requirements of the funding sources.[69] Although various conventions, including, without limitation, financial matters and international sale of goods and securities, are under the private international law domain, private businesses may not take action in signing up to the latter without the state’s support.[70] Thus, financial lawyers undoubtedly play decisive roles in helping firms and officials out during the post-COVID-19 resilience period.

4. Conclusion

The present money is broader than in the Keynesian financial era, and private businesses are more involved in money creation to a larger extent. Money is no longer confined to currency and coins and demand deposits but entails virtual money valued and booked in the same way corporations do for their physical assets.[71] While the public sector regulates the money supply and circulation, private businesses have increased trading in securities and thereby helped create money in the economy. Macroeconomically, the government’s responsibility is supervising the money supply in all forms and job creation.[72] Thus, host private parties and in-between economic entities play crucial roles in revenue creation to be ultimately legalised by the state.

The UK government has taken numerous measures to counter the COVID-19 crisis over the past years.[73] In controlling systemic risk and restoring financial stability, the UK government has regulated the supply of money to initiate more investments in different sectors, thereby offering more jobs within its jurisdiction and other places where the finance takes place.[74] The repurchase of debt securities has alleviated money constraints in the economy.[75] HM Treasures and the Bank of England have taken encouraging measures, including supervision and fiscal and monetary policies, to counter the financial shocks resulting from COVID-19.[76] Monitoring work shall go on for several years to result in satisfactory outcomes. Although it is one of the capital-exporting countries, the UK has settled several legal arrangements with other EU, USA, and Asia capital markets.

For those capital-importing states, including Laos, attention to integrating the financial sector must be put in place to leverage capital investment in their respective jurisdictions.[77] While the COVID-19 pandemic adversely impacted the economy worldwide, the affected zones should have been revived with automation to integrate into more jurisdictions worldwide.[78] Hence, the Lao government should expedite the study on membership of the HCCH and accession to most necessary conventions with respect to trade and finance, utilising available legal advice. The author firmly believes that many Laotian lawyers practising private international law are enthusiastic about getting involved in the public-private exercise to countenance the accession to the conventions under the HCCH deemed necessary to boost financing in the country.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCES

Primary Sources

Case

(1989) British Commercial Law Case, Vol 5 325.

National Westminster Bank Plc v IRC [1995] 1 AC 111, 126 per Lord Templeman; Companies Act (2006)

P Davies Gower and Davies Principles of Modern Company Law (8th edition 2008)

Wrap (UK) Ltd (in liq) v Gula [2006] BCC 626

Legislation

Companies Act (2006)

Insolvency Act 1986 (Order 2003 No. 2097)

Insolvency Act 1986

Trade and Cooperation Agreement, Treaty Series No.8 (2021)

Secondary Sources

Books

Bishop R S, Crapp R H, Faff W R, and Twite J G, Corporate Finance (3rd edition Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group (Australia) Pty Ltd 1993)

Davies L P, Worthington S, Michele E, and Gower B L, Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (10th edition, Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd 2016)

De Filippi P., and Wright A, Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code (Harward University Press 2019)

Ferran E and Look H C, Principle of Corporate Finance Law (2nd edition, Oxford University Press 2014)

Gang J, King S, Stonecash R, Mankiw G N, Principles of Economics, (4th edition Cengage Learning Australia Pty Limited 2009)

Gardner A B, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th edition, Thomson Reuters 2019)

Gullifer L and Payne J, Corporate Finance Law: Principles and Policy (3rd edition, Hart Publishing 2020)

McLeay M, Radia A, and Thomas R, “Money in the modern economy: an introduction” (BOE, Quarterly Bulletin 5, 2014)

Mishan J E and Quah E, Cost-Benefit Analysis, (5th edition Routledge 2007)

Stiglitz E J, “Modigliani and Miller Theorem, and Macroeconomics” (Columbia University 2005)

Turner J, Robot Rules: Regulating Artificial Intelligence (Palgrave MacMillan 2019)

Welch I, Corporate Finance (4th Edition, 2017)

Command Papers

BASEL Master Plan and Implementation Plan for Bank Supervision Development toward BASEL Standards from 2017-2025 (Bank of Lao PDR, November 2017)

Bank of England Measures to Respond to the Economic Shock from Covid-19: Monetary Policy Reduces Bank Rate and Launches New Term Funding Scheme with Additional Incentives for SMEs<Bank of England measures to respond to the economic shock from Covid-19 | Bank of England>accessed on16 June 2022

Bank of England, The Bank of England’s Supervision of Financial Market Infrastructures – Annual Report (for the period 23 February 2017 – 20 February 2018) (2018)

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Eighteenth Progress Report on Adoption of the Basel Regulatory Framework (Bank for International Settlements July 2020)

OECD, The COVID-19 crisis and banking system resilience: Simulation of losses on non-performing loans and policy implication (OECD Paris 2021)

Policy Initiatives in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic – UK: Covid Corporate Financing Facility<HM Treasury and the Bank of England launch a Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF) | Bank of England>assessed on 16 June 2022

Policy Initiatives in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic – UK: Covid-19 Business Interruption Loan Scheme<Chancellor strengthens support on offer for business as first government-backed loans reach firms in need – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)> accessed on 16 June 2022

UNCITAL, Hague Conference and UNIDROIT Texts on Security Interests (New York, United Nations 2012)

UNCITRAL, HCCH and UNIDROIT: Legal Guide to Uniform Instruments in the Area of International Commercial Contracts, with a Focus on Sales (Vienna, United Nations 2021)

[1] Joshua Gang, Stephen King, Robin Stonecash, N Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics (4th edition Cengage Learning Australia Pty Limited 2009) 662-663

[2] Ferran E and Look H C, Principle of Corporate Finance Law (2nd edition, Oxford University Press 2014) 54-56

[3] Ibid (n 1)

[4] Ibid (n 1)

[5] De Filippi P., and Wright A, Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code (Harward University Press 2019) 59-89; Turner J, Robot Rules: Regulating Artificial Intelligence (Palgrave MacMillan 2019) 15 -22

[6] Michael McLeay, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas, “Money in the modern economy: an introduction” (BOE, Quarterly Bulletin 5, 2014) 7-9

[7] Ibid 7-11

[8] Ibid 8

[9] Ibid (n 5) 7-9

[10] Louise Gullifer and Janifer Payne, Corporate Finance Law: Principles and Policy (3rd edition, Hart Publishing 2020 )12-15 27-30

[11] Ivo Welch, Corporate Finance (4th Edition, Printing Source, Inc 2017) 4-7

[12] Companies Act (2006), s 629

[13] Ibid, ss 395(1), 403(2)

[14] Insolvency Act 1986 (Order 2003 No. 2097), s 176A(3)(a)

[15] Ibid (n 5)

[16] ibid (n 1) 725-728

[17] Ibid (n 11) 5

[18] Ibid 12-20

[19] Companies Act 2006, s 542

[20] Ibid (n 10) 12-20, 59-67

[21] E J Mishan and Euston Quah, Cost-Benefit Analysis (5th edition, Routledge 2007)135-138

[22] Ibid (n 10) 59-67

[23] Wrap (UK) Ltd (in liq) v Gula [2006] BCC 626; P Davies Gower and Davies Principles of Modern Company Law (8th edition 2008) para 12-9

[24] Ibid (n 11) 167-170

[25] Ibid 59-67

[26] National Westminster Bank PLc v IRC [1995] 1 AC 111, 126 per Lord Templeman; Companies Act (2006), s 582.

[27] Ibid (n 11) 59-67

[28] Steven R Bishop, Harvey R Crapp, Robert W Faff, and Garry J Twite, Corporate Finance (3rd edition, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group (Australia) Pty Ltd 1993) 646

[29] Ibid 646

[30] Per., Com., 20 November 2023

[31] Per., Com., 20 November 2023

[32] Ibid (n 28), 270-275

[33] ibid (n 1) 725-728

[34] Ibid (n 11) 12-20

[35] ibid

[36] Ibid (n 10) 265-261

[37] Davies L P, Worthington S, Michele E, and Gower B L, Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (10th edition, Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd 2016) 260-280

[38] Ibid 270-273

[39] ibid 275- 280

[40] Ibid (n 10) 285

[41] Insolvency Act 1986, ss 40-41

[42] ibid s 59

[43] Ibid (n 10) 280

[44] Brian A Gardner, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th edition, Thomson Reuters 2019) Ibid

[45] Ibid (n 10) 280

[46] OECD, The COVID-19 crisis and banking system resilience: Simulation of losses on non-performing loans and policy implication (OECD Paris 2021) 9

[47] Ibid 11-13

[48] Ibid 11-13

[49] Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Eighteenth Progress Report on Adoption of the Basel Regulatory Framework (Bank for International Settlements July 2020)

[50] Ibid

[51] Policy Initiatives in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic – UK: Covid Corporate Financing Facility<HM Treasury and the Bank of England launch a Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF) | Bank of England>assessed on 16 June 2022

[52] ibid

[53] Policy Initiatives in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic – UK: Covid-19 Business Interruption Loan Scheme<Chancellor strengthens support on offer for business as first government-backed loans reach firms in need – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)> accessed on 16 June 2022

[54] ibid

[55] (1989) British Commercial Law Case, Vol 5 325

[56] Bank of England Measures to Respond to the Economic Shock from Covid-19: Monetary Policy Reduces Bank Rate and Launches New Term Funding Scheme with Additional Incentives for SMEs<Bank of England measures to Respond to the economic shock from Covid-19 | Bank of England>accessed on16 June 2022

[57] ibid

[58] Ibid 3-5

[59] Ibid 25-37

[60] Trade and Cooperation Agreement, Treaty Series No.8 (2021), art 123 (3)

[61] ibid

[62] Per., Com., 22 June 2023

[63] ibid

[64] BASEL Master Plan and Implementation Plan for Bank Supervision Development toward BASEL Standards from 2017-2025 (Bank of Lao PDR, November 2017)

[65] UNCITRAL, HCCH and UNIDROIT: Legal Guide to Uniform Instruments in the Area of International Commercial Contracts, with a Focus on Sales (Vienna, United Nations 2021)

[66] ibid

[67] Per., Com., 22 June 2023

[68] ibid

[69] ibid

[70] UNCITRAL, Hague Conference and UNIDROIT Texts on Security Interests (New York, United Nations 2012)

[71] Ibid (n 10) 12-15 27-30

[72] Ibid (n 11) 59-67

[73] OECD, The COVID-19 crisis and banking system resilience: Simulation of losses on non-performing loans and policy implication (OECD Paris 2021) 9-11

[74] Policy Initiatives in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic – UK: Covid Corporate Financing Facility<HM Treasury and the Bank of England launch a Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF) | Bank of England>assessed on 16 June 2022

[75] Ibid (n 11) 570-573

[76] ibid

[77] Ibid (n 70)

[78] Ibid (n 5)