Corporate Finance Law: Modigliani and Miller Versus Keynesians. Is the theorem relevant to capital attraction efforts in Laos?

An abridged research paper submitted to the Repository at Dickson Poon Law School, King’s College, London

By: Xaypaseuth Phomsoupha, PhD

Solicitor-at-Law

Researcher & Author

1. Introduction

Law and finance have intensively intertwined since the post-World War II economy, whereby scholars introduced several innovative themes regarding corporate finance affecting a thousand businesses around the globe. Corporate finance is undoubtedly part of economics, whether at the macro or micro level and has evolved the rules of law thereof.[1] Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, the two renowned economists during the 1950s, developed an irrelevance theory in respect of corporate structural capital.[2] The school of thought has influenced the global economic field to a great extent.

This [abridged] paper seeks to reflect the Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller theorem in tax exemption persistently required by investing parties in investment in Laos. As an academic researcher and a financial law practitioner in Laos, the author urges his peer financial lawyers representing the host or investors to take a mainstream approach to corporate finance in advising clients on matters per applicable law.

2. Irrelevance Theory

According to the capital structure theorized by Modigliani and Miller, corporations had their real assets valued not relating to their respective capital structure and value, and government taxes were omitted from the valuation.[3] Regardless of leveraged or unleveraged statuses, companies could generate incomes independently of their equity capital invested by investors. The theorem held that a company with capital comprised of equity and debt could sell its shares at a price as high as that with equity finance did.[4] The company’s value was derived from a without-tax income equation, and thereby, no tax-deductible interests on the debts were subtracted from EBITDA. When omitting the tax item, a Modigliani-and-Miller financier could establish an equal value for the preceding two companies irrespective of their different capital structures.[5] Despite its advocacy, many economists did not agree with the theorem due to its generalization about the law of value.

When compared to the Keynesian macroeconomic theory and the contemporary theories, Modigliani and Miller’s theorem ignored the state supervisory roles, funded by taxes, in managing the economy in developed and developing nations.[6] Furthermore, the state-made law must frame social and/or economic movements. Corporate financing places no exception to the fact that intrinsic components, including, without limitation, accounting, equity and debt, and securitization, are all legislated into law in most jurisdictions in the world.[7] Modigliani and Miller’s theorem was optimistic about information and the market under the circumstances in which they believed that natural or juristic persons could have free-of-charge access to lending institutions for borrowings; businesses did not have to pay taxes to the government, and when companies went bankrupt, the lenders shall have shouldered losses on their own.[8] The theorem did not pass the empirical test in many aspects of the market-oriented economy, whereby a government size tends to shrink, leaving the private sector to grow prosperously. The costs of providing public service by the government emanate from taxation in exchange for securing a safe financial and legal environment for doing business by the private domestic and international parties.[9] Thus omitting tax collection from the national revenues, as suggested by the Modigliani and Miller theorem, is a suicidal approach.

3. Conventional Approach

Social organization of the businesses entails incorporation, in which private parties, including shareholders, creditors, insurers, security providers, suppliers, manufacturers, and consumers, to name but a few, are involved, depending on the nature of the undertakings.[10] The parties mentioned above act with a driving force to dynamically navigate the national economy toward its wealth. In respect of corporate financing, one must understand that risk and reward for participants go in a dyadic relationship pattern. Likewise, the risk is proportionally allocated to each participant, taking into account the reward it expects to reap.[11] To finance a company, each participant shall contribute its respective financial stakes, including equity and debt. The quantification and qualification of equity determine how much a company can raise in debt financing, while the lenders release loans to the borrower on a belief in the credibility of the borrower.[12] Law practitioners specializing in corporate finance law, who advise clients of Lao infrastructure projects, must take the approach hereunder without exception.

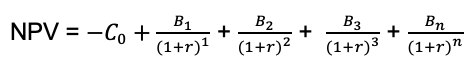

In the contemporary approach, investors, including financiers, apply financial criteria such as Net Present Value (NPV) and Equity Internal Rate of Return (EIRR) to determine their investment decision by having the revenue stream discounted into today’s value and a rate compared to the cost of borrowing for borrower firms and the lending rate for the lenders.[13] The financial criteria are derived from a mathematical equation, which sums up the discounted capital investment during the business start-up and net revenues during the operation period. The formula is illustrated below:[14]

Where denotes;[15]

– NPV, the net present value of the revenues, which investors expect to receive during the entire investment period, is quantified at the investment start-up point;

– C0 the capital investment, comprised of equity and debt,[16] injected by investors and creditors at the start-up investment; the capital investment bears a negative value when it is plugged into the formula;[17]

– B1 to Bn, the net nominal revenue to be received by investors in the relevant years, the annual sum of which is derived from the business’s gross yearly operating revenue minus amounts, including operation expenditures, depreciation, amortization, debt service less deductible interest payment, and corporate income tax; the relevant annual revenue is discounted into the value at the start-up point by being divided by (1+r), which is powered by a cardinal number of the relevant year arranged ordinally from start-up point;[18] and

– r the discount rate or the cost of borrowings, also known as the IRR, results from solving the above equation by making the NPV equal to zero. When making a sensitivity analysis, a financial model operator usually decreases “r” in the best-case scenario and increases “r” in the worst-case scenario.[19]

The company’s valuation serves as a decision criterion for investors. One can use NPV as the financial benchmark; when NPV bears a positive value, the project in question is investible; the higher the value of NPV, the more attractive the investment. But when the NPV is negative, investors will not invest in the project they plan.[20] In deriving NPV at the start-up point, shares known as equity finance of a company shall be quantified not lower than a par value. In Lowry v Consolidate African Selection Trust Ltd,[21] Lord Wright held that the company’s assets expressed in the company’s shares shall not have been lower than the price at registration.[22] The dividend, known as the net revenue and used as the input for establishing the NPV, shall comply with the current accounting standard before distribution to shareholders.[23] Upon the infringement, shareholders are required to return the dividend to the company, and the company’s values are wrongly accounted for.[24] In Wrap (UK) Ltd (in liq) v Gula,[25] Lady Judge Arden concluded that the company defendant proved the irregularity of the distributions.

4. Conclusion

Looking at the Modigliani and Miller theorem retroactively, the author assesses that the idea is financially and legally groundless and does not work for the contemporary environment. For the purpose of corporate finance, reasonable economists establish a mechanism to allocate resources to society on a risk-to-reward basis;[26] rational public administrators create rules acceptable to all financing participants. Financial lawyers must ethically demonstrate their legal professionalism in articulating a quantitative approach to the context of corporate finance, although instructed by clients otherwise.

The host agencies shall understand that the financing arrangement is fair and equitable for all participants. Shareholders, who make a financial analysis before commencing investment, shall take an entrepreneurial liability when the investment costs exceed profits and reap the rewards when the latter is higher than the former.[27] Likewise, creditors receive repayment of loans as agreed and scheduled, regardless of whether the borrower company is at a loss or profitable.[28] In the event that the borrower company goes bankrupt, the creditors recover their interests before the other participants.

For a capital-importing environment like Laos, the host needs more tax revenues to fund its public service. Reasonable investors must refrain from imitating the Modigliani and Miller idea by not seeking unreasonable tax exemptions on matters which should not have been granted. Lenders shall insist that as long as high tax revenues are generated by business activity, the host has no reason to interrupt the tax-revenues stream therefrom. By contrast, if the host is no different from whether or not there is tax income, the protection may be minimized or ceased. Lawyers advising host agencies or investors must balance Modigliani and Miller’s irrelevance theory and the Keynesian law of value.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCES

Primary Sources

Cases

Lowry v Consolidated African Selection Trust Ltd [1940] AC 648

Wrap (UK) Ltd (in liq) v Gula & Anor [2006] EWCA Civ 544

Statutes

Companies Act 2006, s 542

Secondary Sources

Books

Bishop R S, Crapp R H, Tafe W R, Twite J G, Corporate Finance, (2nd edition 1988 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group (Australia Pty Ltd)

Davies L P, Worthington S, Michele E, and Gower B L, Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd

E J Mishan J E and Quah E, Cost-Benefit Analysis, (5th edition Routledge 2007)

Ferran E and Look H C, Principle of Corporate Finance Law (2nd edition, Oxford University Press 2014)

Jackson J and McConnel R C, Economics, (Australian edition 1980 McGraw-Hill Book Company Pty Ltd)

Welch I, Corporate Finance (ISBN 13: 978-0-984004-2-8. v2, 4th edition, 2017)

William A K, Coffee C J, Partnoy F, Business Organization and Finance: legal and economic principles (11th edition, Thomson Reuter/Foundation Press 2010)

Articles

Modigliani F and Miller H M, “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment” (1958) Vol 48, No 3 The American Economic Review <https://jstor.org/stable/ 1809966.103.43.77.13

Stiglitz E J, “Modigliani and Miller Theorem, and Macroeconomics” (Columbia University 2005)

[1] Franco Modigliani and Merton H Miller, “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment” (1958) Vol 48, No 3, 270-275 The American Economic Review <https://jstor.org/stable/1809966.103.43.77.13>accessed 27 May 2022

[2] ibid, 270-275

[3] P L Davies, Sara Worthington, Eva Michele, and L B Gower, Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd, 255-265

[4] Eilis Ferran and Chan Ho Look, Principle of Corporate Finance Law (2nd edition, Oxford University Press 2014) 43-46

[5] William A Klein, John C Coffee, Frank Partnoy, Business Organization and Finance: legal and economic principles (11th edition, Thomson Reuter/Foundation Press 2010)

[6] Joseph E Stiglitz, “Modigliani and Miller Theorem, and Macroeconomics” (Columbia University 2005) 2-8

[7] Ibid, 4-12

[8] Steven R Bishop, Harvey R Crapp, Robert W Tafe, Garry J Twite, Corporate Finance, ( 2nd edition 1988 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group (Australia Pty Ltd)

[9] John Jackson and Campbell R McConnel, Economics, (Australian edition 1980 McGraw-Hill Book Company Pty Ltd) 141-146

[10] Ivo Welch, Corporate Finance (ISBN 13: 978-0-984004-2-8,.v2, 4th edition, 2017) 11-49

[11] ibid, 20-25

[12] ibid, 24

[13] ibid, 11-49

[14] ibid, 45

[15] ibid, 11-49

[16] Companies Act 2006, s 542

[17] E J Mishan and Euston Quah, Cost-Benefit Analysis, (5th edition Routledge 2007), 135-138

[18] ibid, 136

[19] ibid, 137

[20] ibid, 135-138

[21] Lowry v Consolidated African Selection Trust Ltd [1940] AC 648, 679

[22] ibid

[23] ibid

[24] ibid

[25] Wrap (UK) Ltd (in liq) v Gula & Anor [2006] EWCA Civ 544, 277

[26] Steven R Bishop, Harvey R Crapp, Robert W Tafe, Garry J Twite, Corporate Finance, (2nd edition 1988 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group (Australia Pty Ltd)

[27] Ibid,

[28] Ivo Welch, Corporate Finance (ISBN 13: 978-0-984004-2-8,.v2, 4th edition, 2017) 11-49